If you loved Caesar’s Gallic wars in school but now, since the children have come along, have had less time to pursue your Latin reading, then this is for you. You would hardly think that it’s a huge market but apparently “Winnie Ille Pu” is a New York Times bestseller.

Reading etc.

Looking out for your Immoral Soul

At mass yesterday we had a reading from St. Paul to the Corinthians. Consider the following:

“What is expected of stewards is that each one should be found worthy of his trust. Not that it makes the slightest difference to me whether you, or indeed any human tribunal, find me worthy or not. I will not even pass judgement on myself. True, my conscience does not reproach me at all…”

Doesn’t your heart go out to the Corinthians? Wasn’t St. Paul an annoyingly smug correspondent? He comes to a sticky end and one can’t help feeling that a small number of Corinthians were wondering whether Paul, on arrival in heaven, got busy telling God how to manage matters better. I once heard a monk say that St. Paul was necessary for the organisation and administration of the early church but that he must have been tedious and irritating company.

In his sermon, the priest told us all not to worry, all would be well. Which was comforting but not quite as well put as the Gospel itself:

“Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin: And yet I say unto you, that even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these. Wherefore, if God so clothe the grass of the field, which to day is, and to morrow is cast into the oven, shall he not much more clothe you, O ye of little faith? Therefore take no thought, saying, What shall we eat? or, What shall we drink? or, Wherewithal shall we be clothed? (For after all these things do the Gentiles seek:) for your heavenly Father knoweth that ye have need of all these things. But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you.

Take therefore no thought for the morrow: for the morrow shall take thought for the things of itself. Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof.” [King James Bible version]

That’s probably enough material for your immortal soul for one day.

I can’t get this out of my head

Being sick, poor and marginalised. Not very nice.

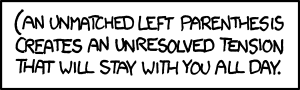

OCD Pedants Will Love This

Reading

“The Death of the Irish Language” by Reg Hindley

Mr. Waffle bought this when he was poor and living in Paris. I think because he is a masochist. The book examines the health of the Irish language in 1985/86 by DED. This is not, in fact, as tedious as it might sound. One of his research methods was to hang around playgrounds listening to the local children to see whether they were really speaking Irish to each other – testing the truth of the census and, more particularly, the deontas returns. I can see this being a quite effective methodology but one probably not open to older male researchers today.

The author can’t help himself from lamenting the fact that women and men from the Gaeltacht have no concern about finding another Irish speaker when looking for love and non-native speakers are constantly marrying in and diluting the strength of the language – not to mention the damage that the television and the roads do. This is gently funny from time to time though not deliberately so.

The author is a linguist and an Englishman from Bradford. He gives a phonetic English pronouciation of Irish place names for the convenience of the English reader, one assumes. I was amused to see him say that Cois Fharraige might be pronounced Cush Arriger in English. It mightn’t. That intrusive final “r” is entirely English. Oh that a linguist should make such an error.

All in all I found it surprisingly enjoyable but a little depressing. I don’t want the Irish language to die. And even though, the other night my loving husband and I sat on the sofa and watched our children sing songs in the first national language and do some Irish dancing (a long way from Riverdance), in a manner that would, I am sure have made De Valera proud- it’s not really much good, if Irish is on its deathbed as a native language. The author points out that in general Irish people are positive towards the language and do not want it to die out but essentially they feel that the duty of saving it falls to civil servants and school children.

On the back of the book is a quote “Oh the shame of Irish dying in a free Ireland.” I do think that this may be our generation’s tragedy, that Irish as a living language will die on our watch. Of course, what with the IMF and that there is a lot of competition for what this generation’s tragedy might be. I suppose we’ll have to see how the recently published 20 year strategy on the Irish language pans out – come back to me in 2030.

“Death of a Macho Man” by MC Beaton

Left behind by my sister following babysitting adventure. All her tired brain could face after a day with my children. Undemanding.

“Another September” by Elizabeth Bowen

This is set in County Cork at the time of the War of Independence. I found it tough enough going and, for a slender volume, it took me quite a while to read. If you’ve ever read “Cold Comfort Farm” by Stella Gibbons, you will know that she satirically asterixes descriptive passages which are particularly fine. I can’t help wondering whether this was the very book she was satirising, take this passage selected at random:

“The screen of trees that reached like an arm from behing the house – embracing the lawns, banks and terraces in mild ascent – had darkened, deepening into a forest. Like splintered darkness, branches pierced the faltering dusk of leaves. Evening drenched the trees; the beeches were soundless cataracts. Behind the trees, pressing in from the open and empty country like an invasion, the orange bright sky crept and smouldered. Firs, bearing up to pierce, melted against the brightness. Somewhere, there was a sunset in which the mountains lay like glass.”

I think that is quite dreadfully overwritten, even allowing for the changes in tastes over the 80 odd years since it was published. And there is a lot of this kind of thing to wade through. As I read on, I remembered that I had found “The Death of the Heart” a real struggle. What saved this book for me was the context. It was interesting. Firstly, it was written from the point of view of an Anglo-Irish family. They considered themselves Irish and disapproved very much of the English whom they found vulgar: obsessed by their digestion and by money.

And at one level, where else would this Anglo-Irish family be from? There they were in their family home on the site where their ancestors had lived since the 1600s (assumption based on the belief that Danielstown is Bowen’s Court, Elizabeth Bowen’s family home). But yet, they seem very alien to me. Even allowing that everyone from the 1920s would seem very foreign, this is another layer of separation.

Co-incidentally, I went to an exhibition in the National Photographic Archive called “Power and Privilege: The Big House in Ireland”. Mostly these photographs of the landed gentry, their houses and their households dated from the period between 1900-1910. They provided images to go with the text of Elizabeth Bowen’s book. To my surprise, what I found fascinating about the exhibition was not the houses but the staff. Their uniforms, the women’s lace hairpieces and their number; those houses needed armies of servants. Under one picture, there is a comment that all of the servants in the picture are English. The gentry, or this particular family at all events, didn’t want Irish servants; one can only imagine the rancour this must have caused in a poor country where employment was scarce. In England, there was no such thing as the absentee landlord. In Ireland, many Anglo-Irish families never visited their Irish estates at all.

All this by way of saying that the attitude to the Big House (and its inhabitants) in Ireland is ambivalent, some were good landlords, many were not but all of them were different. This book captures that rather well. These people suspended between Ireland and England, neither one thing nor the other. I was fascinated to see that they appeared to be just as terrified of the Black and Tans as any other Irish person despite the fact that they were entertaining British army officers over tea and tennis. In this story, there is an exquisitely awkward moment when Lois, our heroine, inquires of a family (presumably tenants, though possibly neighbours) whether they have any news of their son who both parties know is on the run. I would quote it but it is too bloody long to retype. Bowen is good on interactions between people and all that is implied by silences and unfinished sentences and the half truths which make up polite conversation in difficult circumstances.

In the 60s, the longest Georgian terrace in Europe was in Dublin. It was knocked down for a modern concrete construction. In the face of some outrage (the terrace was pretty, the replacement was not) a government Minister said that he was delighted. He regarded this as one in the eye for the oppressor. This attitude is a very direct descendant of the one which burned down some 200 big houses up and down the country during the war of independence. I think we have made our peace with the big house now, they’re mostly filled with luxury hotels. When Paddy Kelly put up a development near Castletown House, in Kildare, he said, “It was time the Irish went through the front gate.†I’m not sure that he considered the Anglo-Irish to be really entirely Irish.

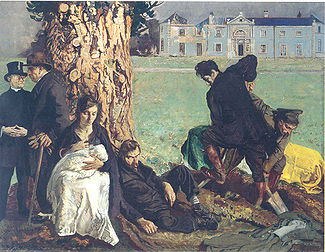

The introduction is by Victoria Glendinning, an English woman. She says, “I don’t want to spoil the book by revealing the climax. But I would ask you, as you read, to notice the accumalative imagery of fire and burning.” Any Irish person, of any description would not need that – you know, almost from the first chapter that the house will be burned. This picture, “An Allegory”, by Seán Keating should be used for the cover of the book:

“At Home” by Bill Bryson

I love Bill Bryson and this is a very readable, entertaining book but I feel that it is, slightly, painting by numbers. He’s done better and he certainly got full value for his subscription to the dictionary of national biography in drafting this tome. There are a couple of places where things are repeated and it could, perhaps, have done with more thorough editing. All that said, I enjoyed it very much and learnt some new things. I found myself itching to get back to it and it was a great Christmas holiday read. Bryson has an infectious enthusiasm for everything and if you ever thought you would like to know more about sewers there is no better man to talk you through them. This is, essentially, a history book. It is organised around the rooms in his house. So, for example, in the bedroom he covers sex, childbirth, illness and death over the years and the changing perceptions and processes from about 1600 to the 20th century. Sometimes one feels that interesting facts he has learnt are somewhat shoehorned into the format but, broadly, it works.

“Over Sea, Under Stone” by Susan Cooper

My sister got this for the Princess for Christmas, she didn’t fancy it so I picked it up and read it myself. I really enjoyed it – more for the delightfulness of childhood summers that it evoked than for the plot, it must be said. I went out the next day and bought volume 2 of the series which is really all you need to know.

“The Dark is Rising” by Susan Cooper

Volume 2 of the series which began with “Over Sea, Under Stone”. Oh, the disappointment. All dull fantasy (and I don’t object to fantasy, just dull fantasy), none of the lovely seaside holiday feel of the last book and only one character carried over and that one among the least engaging. I think I will be leaving the rest of the series alone.

“JPod” by Douglas Coupland [New Year’s Resolution Pile]

Sitting on my bedside table since 2006 hasn’t done this book any favours. It’s supposed to be bang up to the minute and I’m sure it was in 2006 but putting technology at the centre of your book turns out to be a problem. One of the characters describes kodak photo share as like being transported back to 1999. Hmm, but this book has no twitter and no youtube and it features game designer nerds who would presumably use all these things. Catastrophically dated. Also, annoyingly self-referential. These characters talk about Douglas Coupland a lot and he has a bit part.

I used to really like his books and I have read a lot of them but this book lands on the wrong side of the line between pretentious and original. Disappointing.

“Una Bambina e Basta” by Lia Levi [New Year’s Resolution Pile]

This is really a novella and the fact that I took two years to finish it is more a reflection of the fact that it is in Italian than the content itself. It’s about a little Jewish girl who ends up hidden in a convent during World War II and about how she and her family get through the war. It’s autobiographical and I find the author’s childish voice a little tedious. I suspect although it has merit, it’s the kind of book I wouldn’t have particularly enjoyed even had I read it in English. Rather annoyingly, my mother-in-law is reading it also and she loves it. My mother-in-law sits Leaving Certificate courses for fun and this book is on the Italian course. Which reminds me of a rather amusing anecdote she once told me. Regular readers will recall that my husband’s next door neighbour when he was growing up is now a well-known novelist. My mother-in-law decided to sit the Leaving Certificate English paper for fun and she relied on the young pre-novelist, then a Leaving Certificate student herself, to supply details of the syllabus. This worked very well until the night before the examination when the pre-novelist admitted to my mother-in-law – “Oh dear, I forgot to tell you, we had to do a play as well.”

“Jane Austen Ruined My Life” by Beth Patillo [New Year’s Resolution Pile]

I cannot tell you how dire this book was on every level. I received it as a present from someone who has never previously failed to deliver. Which, of course, makes it worse. Good title though.

“Better: A Surgeon’s Notes on Performance” by Atul Gawande

When I was at my parents’ house in Cork over the weekend, my father said to me, “I’m sure you gave me a Christmas present, just remind me, what was it.” It was this book and a companion volume “Complications”. My father is impossible to buy for and we almost always end up giving him books. This is guilt inducing as he has a huge pile of worthy books which people think he might like to read (mostly they tend to cover sailing boats, steam engines, medicine and Cork usually with a dash of photography thrown in) and which only serve to unnerve him at every turn as he tries to polish off his daily crossword. However, I was delighted when he said, “Oh I thought that they came from your aunt, they were very good.” I was delighted also to clarify that I was the brilliant donor. I found this volume on the couch and, on the basis of his recommendation, read it. It’s an interesting read and a very easy one, the author has a very accessible style and seems to be as much a writer as a doctor which is an unusual combination. He writes about medical matters in a very insightful way and certainly gives the lay reader a number of new perspectives. One of the essays in this series is about cystic fibrosis – my father particularly recommended it and it stuck in my mind also. I think one of the reasons for this is that, in Ireland, cystic fibrosis rates are high. A girl in my class in school died from it. The author used CF as an example of the finding that medical success rates are in the classic bell curve shaped graph. He said that we expect the graph to be fin shaped with good results bunched towards the right of the graph but this is not actually the case. He then goes on to discuss how to use this kind of information to improve performance. In the best performing case in the US, there is someone who is 67 who has cystic fibrosis. When you consider that my former classmate died in her 20s that seems amazing. Gosh, I am making this sound quite dull but it’s really not. I recommend it and, what’s more, I’m going to find the companion volume to read when I go to Cork next.

Possibly, You Had To Be There

I was at a very entertaining dinner party recently. As my fellow diners included, inter alia, someone who works for the IMF and a banker, there was an explicit agreement to steer clear of the bailout. Instead, we talked about books which was quite lovely. At one point our hostess went round the table asking us to recommend a really, really good book that was worth reading (if you care, I said “Gilead” by Marilynne Robinson) and not one but two people recommended “La Bête Humaine” by Zola. Our hostess, naturally interested, asked what it was about. There was a horrified silence. It was a long time ago. I did sympathise as I often only retain the vaguest impression of what I have read but still. Vaguely reminiscent of David Lodge’s “humiliation“.